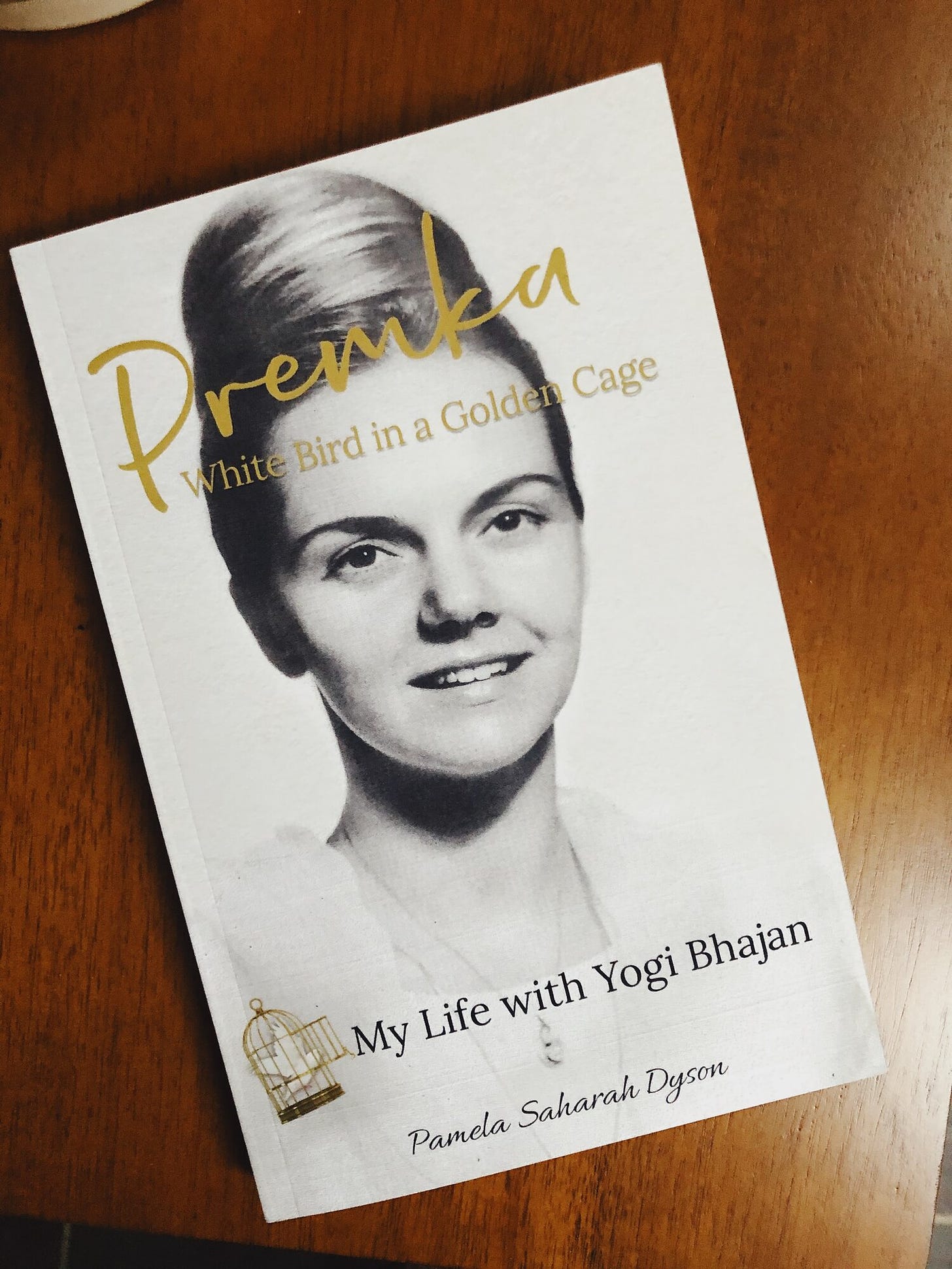

Note to reader. I have been a practitioner of Kundalini yoga since 2013 and completed the IKYTA/KRI teacher training over a two-year period, from 2013 to 2015. While there have been lawsuits, stirrings, rumors, and speculation around whether Yogi Bhajan, the founder of Kundalini Yoga, abused his followers and members of the 3HO community for years, the release of the book Premka: White Bird in a Golden Cage: My Life with Yogi Bhajan, a memoir of Pamela Dyson’s nearly two decade account of working for and serving as Yogi Bhajan’s private secretary, in which she was abused psychologically and sexually, definitively broke open the conversation, forcing a reckoning within the Kundalini community similar to what has happened in other communities and professions in the #MeToo era. This is my response to that as a student and teacher of this yoga. This is not meant to be an eloquent post; it’s meant to add clarity around where I stand, and how I, and my organization, Tempest, which uses Kund…

© 2025 Holly Whitaker

Substack is the home for great culture