Transitions, part 2: 21 thoughts on how to be lost

"An incomplete collection of potentially imprecise and contradictory field notes on how to be lost, or how I tried to be lost"

“More often, we need to leave the old without any promise of the new, need to spend time as forest dwellers, just surviving.” - Marianne Woodman

This is a continuation of this column—the second installation of a three-part series on transitions. (Third part is still to come.)

Introduction

This piece has been a slog. It’s also extremely long and I would caution against reading it all at once?

What I set out to write (“A list of the things I found useful over the course of a life transition that seemed to have no end or purpose”, as promised here) sounded doable. I used to be good at listicles, and if you were to come to me and say “I feel like I’m in between two lives can you give me some advice?” I’d make you a spreadsheet. In other words, telling you ‘here’s what I did to manage a really long liminal period’ felt like a very easy and potentially fun exercise, like I was going to make you a list of the best churches to visit in Rome.

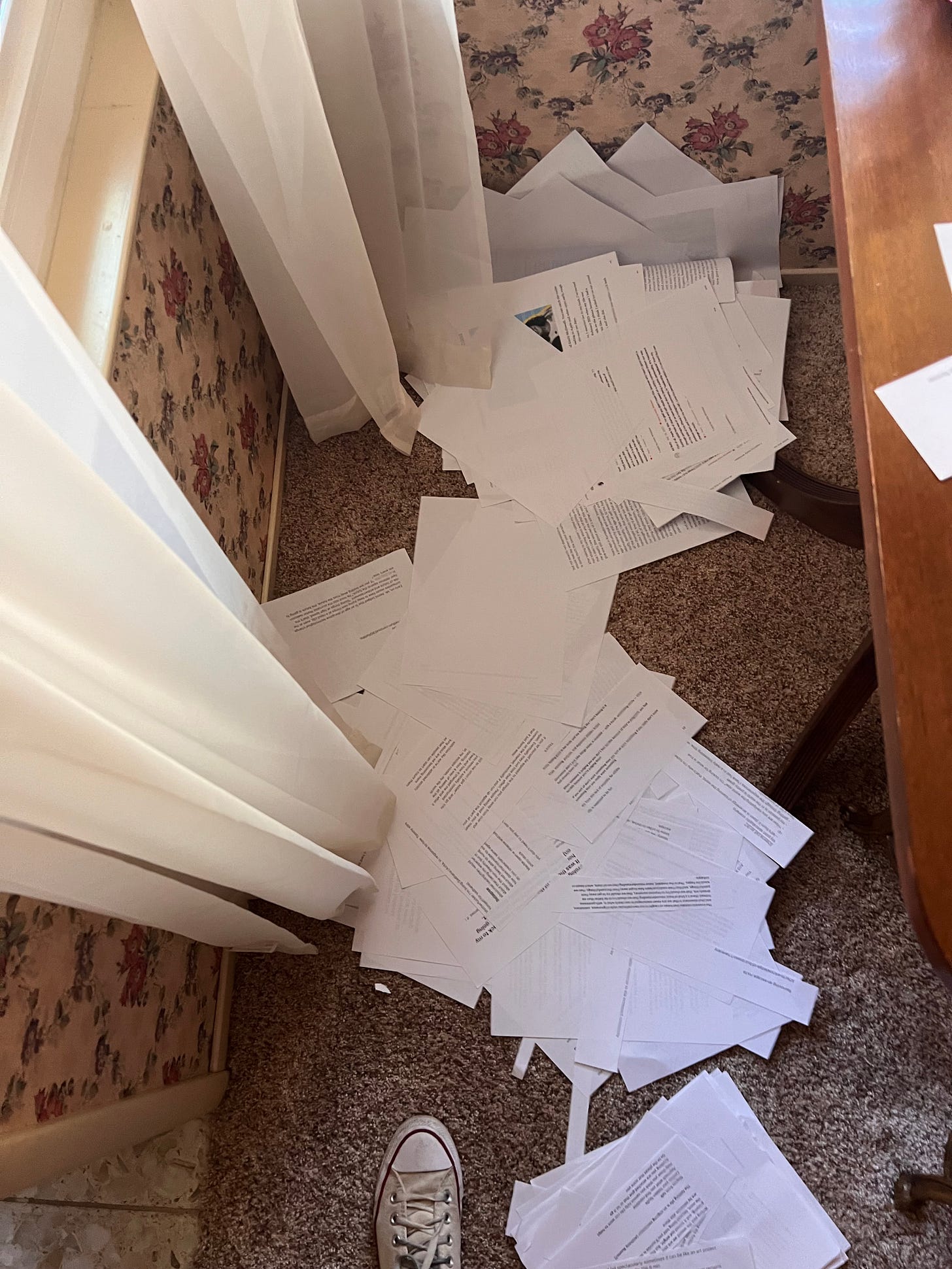

But then that simple list turned into a brain dump of the notes I took and the articles I clipped over a two-year period in an effort to make sense of what was happening to me (feeling lost/unmoored/directionless/existential dread for an ‘excessive’ amount of time), and what was happening to the world (everyone and everything appearing to be extremely fucked up), and because both of these things are still mysteries to me (myself, the world), the list of “things” propagated from ten to 20 to 30 and then blurred into something else. Trying to write this piece was like trying to bake a cake when I hadn’t stirred the batter, or like trying to make my brain work in a way it now refuses to. I cannot simplify, boil down, or arrive at universal truths the way I once could.

So. I don’t have “a list of things that I found useful over the course of a life transition that seemed to have no end or purpose”; what I have instead are some tools and some advice I would have given myself if I’d had it, but mostly a lot of thoughts I wrestled with, ideas I developed, patterns I observed, and changes I witnessed, during the period of time when my life was chronically in-between and the rest of the world seemed that way, too.

So. Take this less as some definitive list or set of truths; treat it more like a non-linear, incomplete collection of potentially imprecise and contradictory field notes on how to be lost, or how I tried to be lost. Be assured this is a mess of thoughts, and it absolutely should have been broken up into smaller essays.

Rudolph Bahro said “When the forms of an old culture are dying, the new culture is created by a few people who are not afraid to be insecure,” and Krishnamurti said, “It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.” The final thing I’ll say about this specific piece: I am not trying to help you feel better, or make something more of your confusion or in-betweenness, should that be where you are. Instead, my point (in this piece, in general) is: I think the future of our society, culture, species, and planet depends on the extent to which we all allow our identities to be destroyed and ourselves to be lost. Which is to say, if you’re feeling ungrounded or lost or in-between, I think that just means you’re a fertile patch of ground the world desperately needs, and I’m so sorry and happy for you.

Finally: Much has been written on this topic, and I’ve read a nice portion of it. There’s a resource list at the bottom, and please feel free to add yours in the comments.

21 thoughts on feeling lost for an endless period of time

1. First, the money thing

Because enough of you will read this and think this lady had some kind of financial privilege in order to lose her shit and fuck off for a few years, I want to assure you I did. I own my home and my mortgage is reasonable. I had a small retirement account started, I had savings, I had no debt. I had a meager severance from Tempest (that was subsidized later by the temporary CEO, who got money from the sale of Tempest while I did not and who graciously gave me half of her paycheck from the sale). I had money coming in from my first book, including royalties but also a bonus payment because QLAW sold better than expected. I had a few speaking gigs, some contract work, and I started my Substack last January which has brought in some income. I currently do not make enough money to cover my expenses after taxes, but I’m also not worried about that because I have better than average earning potential (I could create a course, start coaching again, really pump up this Substack, try and get speaking gigs, etc.), and I have an existing book deal. I say all this not to justify my worth or show you my financials or anything like that, but to give you a baseline to operate from.

As you’re reading this keep in mind two things: (1) I had time and resources and better than average future prospects, and (2) I used all of my savings, I was willing to drain my retirement and sell my house to buy time (though I have not had to), I forewent a good number of experiences and expenses, and I took a significant amount of risk on myself. Or: I had privilege and I made some sacrifices.

All that being said, financial insecurity has been a real theme, I have worried about how I’ll make a living as a full-time writer or if I will ever make an ‘adequate’ living again, and it has been uncomfortable and scary depleting what I’d saved up. But I also have refused to let financial security be the primary driver of my choices, which allowed me to walk away from situations I found to be highly compromising of my values, and allowed me to only pursue things I found to be full yeses. I discovered over these past few years I would rather be in integrity than be rich or even solvent.

I also value comfort, I like nice things, I don’t believe in zero-sum realities, and I have an abundant mindset (in less a law-of-attraction, more adrienne marie brown kind of way). If I want to believe in a world where everyone is taken care of and everyone has a sense of abundance and everyone gets to make a living doing things that inspire them rather than destroy them, I have to live that principle myself.

Lastly, and this kind of goes to point #4 (“Values”): I have a very different idea of what enough is now, and it’s a much smaller sum than it used to be.

2. Healing as performance

I think for a lot of reasons I don’t need to name, we’re convinced what a sane person does is heal and then turn that healing into some kind of product, and I don’t mean something like a fitness app (which I do indeed mean), but also a better job or a better ass or a better personality. All failure or struggle or pain or inertia gets reduced to what we make out of it, what we transmute it into, and what we become after, and therefore experiences don’t hold intrinsic value, they are only a currency worth what we exchange them for. As Caleb Campbell put it in this interview, we’re awash in a culture that subtly and unsubtly encourages us to reduce all our healing to a kind of performance.

In the beginning, I felt pressure to do something with what was happening to me—to turn it into a book or podcast or an op-ed or a really compelling Instagram post or a life that was better than the one I had before. There was a true period of time—about six months in—when I hadn’t really changed all that much or done much of anything to improve my situation and by objective appearance, I was just fucking off all day every day. And I kept thinking to myself: It’s been a long enough time, shouldn’t you be talking about this? Shouldn’t this be an integrated lesson by now? Which is not a kind of healing, but a kind of cruelty.

I start here with this because as you read through the rest, I want to be clear that part of what allowed me to move forward was dropping the illusion that I was supposed to turn my experience into something more than it was, and I say this not to release me from some kind of judgment or assure you this column that is written as a product of my experience of being lost is not the product of commodifying my experience of being lost, but simply to tell you: it is a bad and destructive idea to think we are supposed to turn our healing into anything beyond the experience of it.

You don’t have to make anything out of this. Just be lost.

3. Feeling like yourself

In Haley Nahman’s essay, On Feeling “Like Yourself”, she does a much better job than I could describing what it means to feel, or not feel, like oneself. A few poignant quotes: “I don’t think ‘not feeling like myself’ has to do with being sad necessarily, I suspect it has more to do with comfort and control. I feel like myself when I recognize the terms of my existence and feel comfortable navigating myself within them.” And: “I approve of my current desires, therefore comprehend myself.”

I have at many points in my life not felt “like myself”, mostly in small and fleeting ways, like when I don’t get enough sleep or I’m traveling or I’m in some kind of depression. There’s usually a relatively quick reprieve, some moment of “Oh there I am again,” and in a way, I was waiting these past two years for that exact moment: I would know my in-between had ended when I began to recognize myself again. Only that makes it sound a lot nicer than I actually was with myself about it. It was more like: Why the fuck haven’t you snapped out of this yet?

Early on, I imagined feeling “like myself” again would be just that—an again—wrought through a return to some former behavior. I would be me again when I was producing, working on my next project, on the schedule I desired, with an intact sense of purpose. I’d be me again when I was forward driving or getting a consistent paycheck or doing my hair for a reason. But that return never materialized. I didn’t wake up one day spellbound by the next idea or vision of my life to work toward. Instead I just kind of slowly creamed outward like spilled yogurt.

If I take something Haley said—that we more easily comprehend ourselves when we approve of our desires—and apply it here, it follows that because in my in-between, I did not approve of my desires (which were mostly to be left alone and not do very much work and not try very hard at anything at all), there had to be some known desires I did approve of, and if I could recapture them then I would comprehend myself, and feel like myself once again. But then eventually I started to think: What if the known desires are dead for a reason? What if there are new unthinkable desires, and I just haven’t given myself the grace to find them?

I can confirm that not feeling like yourself is a special kind of hell, and it’s a special kind of hell mostly because we define health and functioning and flourishing through a really narrow lens, one that assumes that we know who we are and we know where we’re going, or at least that we know what we want, or at the very least that we’re still productive and contributing members to society. If we don’t have those things, we assume a lack, a thing we’re supposed to correct for. No one ever tells you to just absolutely lose your shit and fuck off and be confused, they tell you to make a plan. And no one ever says this is so fun not knowing who I am at all anymore—what we say, or what I said, is I feel like such a fucking loser.

Refer back to the Bahro quote above. Maybe this sounds like a detour from everything I’ve just said, but I see the idea of knowing ourselves, and the idea of a future being created by those unafraid to be insecure, as inseparable statements. We already have a world where people are trying all the time to know themselves through comfort and familiarity and unexamined desires. What kind of world would it be if instead, everyone tried to lose themselves, tried to not know who they were, and accepted that not feeling “like their old self” was just exactly that: not being their old self?

I think I am saying if you don’t feel like yourself, even if it’s been years, perhaps that’s a sign of health, an opening and an offering, and not a sign that something needs to be fixed.

4. Values

Which brings me to values, because when you’re desperately trying to resurrect the familiar in order to save yourself from the skin-flaying insecurity that is the in-between, or fast-forward to what comes next, you aren’t necessarily questioning whether you even hold the same values you once did.